In fact, a new design concept that supports trauma affected individuals is starting to gain traction. Jonathan Farrell and Renee Weeks presented on this concept at the Vermont Office of Economic Opportunity Conference in 2019. The term “trauma-informed design” is a concept that gives architects and interior designers focus on integrating the principles of trauma-informed care into their practices. The goal of this design concept is “to create spaces that are welcoming, demonstrate a safe environment, and provide some degree of privacy, while at the same time not interfering with staff’s need to monitor residents’ behavior.”

Garcia of 34h goes on to say “Trauma-informed design incorporates the principles of trauma-informed care: empathy and understanding. It is an effective approach to designing spaces where trauma-experienced individuals may spend time, such as hospitals, Veterans Affairs facilities, behavioral health centers, and social service facilities. The goal of trauma-informed design is to create environments that promote a sense of calm, safety, dignity, empowerment, and well-being for all occupants. These outcomes can be achieved by adapting spatial layout, thoughtful furniture choices, visual interest, light and color, art, and biophilic design.”

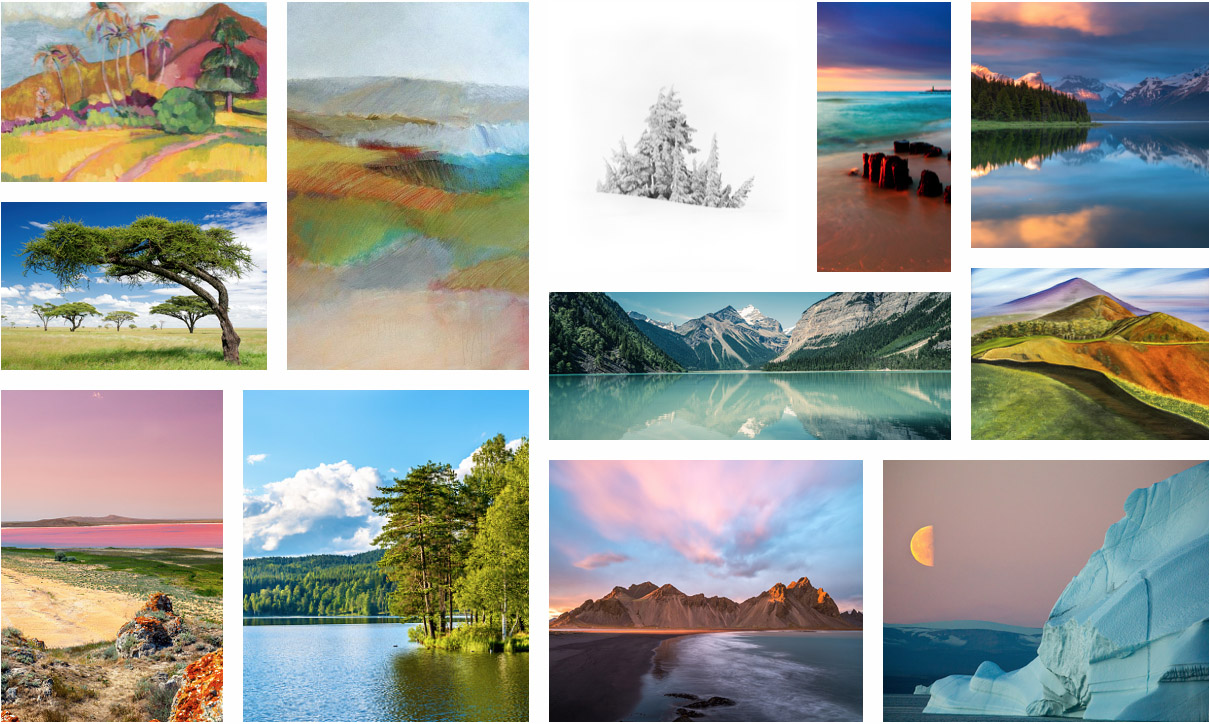

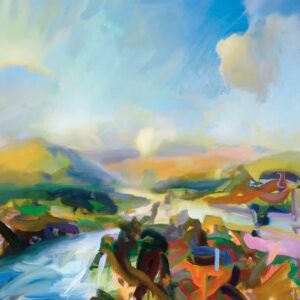

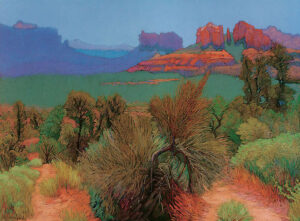

For artwork specifically, Garcia describes the need for nature, painting, and photography as means of creating a visual distraction, much like the images below. Farrell and Weeks go on to explore the need for attention to selecting art that “does not convey meaning or symbolic significance that would generate or arouse negative feelings.”

This is design concept underscores the importance of artwork selection. It is imperative that artwork selection supports the community being served, and is considered part of the treatment, the space, and the program.

How can we help bring your next project to life?